Lesson 3 Box Models and Combinations

Motivating Example

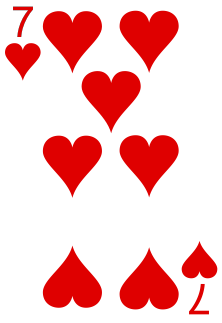

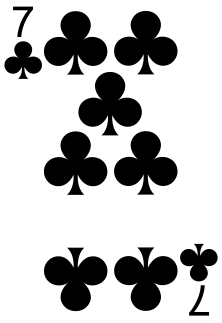

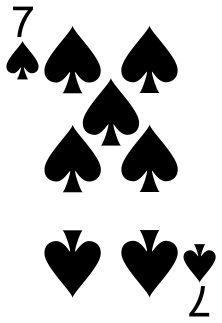

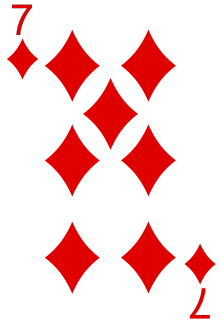

One of the most coveted hands in poker is a four-of-a-kind, which is when the hand contains all four cards of a particular rank. For example, the hand below is an example of a four-of-a-kind, since it contains all four 7s in the deck. (The last card, called the “kicker”, can be any other card.)

In this lesson, we will calculate the probability of a four-of-a-kind in two ways: (1) using methods that we have already learned and (2) using combinations, which is a new method that will be introduced in this lesson.

Theory

Many counting and probability problems can be reduced to a box model. In a box model, there are \(N\) tickets in a box, and we draw \(n\) tickets from the box.

For example, three rolls of a fair die can be modeled as \(n=3\) draws from the box \[ \fbox{$\fbox{1}\ \fbox{2}\ \fbox{3}\ \fbox{4}\ \fbox{5}\ \fbox{6}$}. \] In order to accurately model how dice behave (i.e., the outcome of one die roll does not affect the outcome of another), we have to place the ticket back in the box after each draw. In other words, the \(n=3\) draws are made with replacement.

In other situations, the draws are made without replacement. For example, consider four friends who draw names from a hat to determine whom each person’s Secret Santa is. If we call the four friends “1”, “2”, “3”, and “4” (their actual names are unimportant, as far as probability is concerned), then we can model the Secret Santa game as \(n=4\) draws from the box \[ \fbox{$\fbox{1}\ \fbox{2}\ \fbox{3}\ \fbox{4}$}. \] Since every person has exactly one Secret Santa, the draws must be made without replacement. Once a Secret Santa has been chosen for person 3, we remove \(\fbox{3}\) from the box so that they do not end up with two Secret Santas.

Using the multiplication principle (Theorem 1.1), we can count the number of ways to draw \(n\) tickets from the box \[ \fbox{$\fbox{1}\ \fbox{2}\ \ldots\ \fbox{\(N\)}$}. \]

- If drawing with replacement, the number of possible ways is \[ \underbrace{N \cdot N \cdot N \cdot \ldots \cdot N}_{\text{$n$ terms}} = N^n, \] since we have \(N\) tickets to choose from on each draw.

- If drawing without replacement, the number of possible ways is \[ \underbrace{N \cdot (N-1) \cdot (N-2) \cdot \ldots \cdot (N-n+1)}_{\text{$n$ terms}} = \frac{N!}{(N-n)!}, \] since the number of tickets remaining in the box decreases by 1 on each draw.

For example, if we assign a number 1 to 52 to each card in a standard playing deck, then a poker hand can be modeled as \(n=5\) draws, without replacement, from the box \[ \fbox{$\fbox{1}\ \fbox{2}\ \ldots\ \fbox{52}$}. \] The number of possible poker hands is \[ \frac{52!}{(52-5)!} = 52 \cdot 51 \cdot 50 \cdot 49 \cdot 48 = 311,875,200. \]

How many of these possible outcomes result in a four-of-a-kind? Here is the reasoning:

- Let’s start by assuming that the first four cards in the hand are the four-of-a-kind and the

last card is the kicker.

- The first card can be any one of the 52 cards.

- Once we have chosen the first card, the rank of the four-of-a-kind is determined. The second card must be one of the 3 remaining cards of the same rank.

- The third card must be one of the 2 remaining cards of that rank.

- The fourth card must be the 1 remaining card of that rank.

- The last card, the kicker, is one of the other 48 cards in the deck.

- We assumed that the kicker was the last card in the hand. But the kicker could just as well have been the first card in the hand. In fact, the kicker could have been in any one of 5 positions. So we need to multiply everything by 5 in the end.

So the probability of a four-of-a-kind is \[ \frac{(52 \cdot 3 \cdot 2 \cdot 1 \cdot 48) \cdot 5}{52 \cdot 51 \cdot 50 \cdot 49 \cdot 48} \approx .00024. \]

This calculation was complicated because we had to consider the different orders in which the cards might be drawn. It is often easier to ignore the order when counting outcomes. That is, we treat \(\fbox{1}\ \fbox{3}\ \fbox{4}\ \fbox{5}\ \fbox{8}\) as the same outcome as \(\fbox{3}\ \fbox{5}\ \fbox{4}\ \fbox{1}\ \fbox{8}\); we do not double count different reorderings of the same draws. Fortunately, when the draws are made without replacement, the unordered outcomes are also equally likely, so it is equally valid to count unordered outcomes as ordered ones for the purposes of calculating probabilities. If we ignore order when counting, we say that “order doesn’t matter”.

Example 3.1 (Commitee Chair Example) How many different chaired commitees of \(k\) people can be formed from \(m\) people? A “chaired committee” is a committee where one person has been designated as chair. Two possible committees consisting of the same \(k\) people are considered different if they have different chairs.

One way to form the chaired committee is to first choose the \(k\) people, and then designate one of the \(k\) people as chair. By the multiplication principle (Theorem 1.1), there are \[ \binom{m}{k} \cdot k \] ways to do this. (Note that we only care about who is on the committee, not the order in which they were selected to be on the committee, so for the purposes of this problem, order does not matter.)

Another way to form the chaired committee is to first choose one of the \(m\) people to be chair, and then choose the \(k-1\) other members from the remaining \(n-1\) people. There are \[ m \cdot \binom{m-1}{k-1} \] ways to do this.

Both answers are correct, so they must be equal to one another, yielding the useful combinatorial identity \[\begin{equation} k \binom{m}{k} = m \binom{m-1}{k-1}. \tag{3.2} \end{equation}\] The “story proof” (about the chaired committee) proves this identity. Of course, we could also prove this identity by expanding the combinations using (3.1) and simplifying. One of the Essential Practice problems asks you to do this. However, this algebraic proof does not give much insight into why the identity is true. The story proof gives us the insight that will help us remember this identity in the future. We will use this combinatorial identity many times throughout this book.Now, let’s revisit the probability of a four-of-a-kind using combinations. If we ignore the order of the cards in the hand, there are \[ \binom{52}{5} = 2,598,960. \] possible poker hands. (Binomial coefficients can be calculated using Wolfram Alpha.) Notice how much smaller this number is than the 300+ million ordered poker hands. That is because when order matters, each distinct (unordered) poker hand gets counted \(5! = 120\) times, once for each possible way of reordering the 5 cards in the hand.

How many “unordered” four-of-a-kind hands are there? Here is how to count them:

- There are 13 ranks (Ace through King). Any one of these ranks could be the rank for the four-of-a-kind.

- Once we have chosen the rank, that completely determines 4 of the 5 cards in the four-of-a-kind hand. There is only one way to include all 4 cards of a given rank, since we are no longer concerned with the order in which they are drawn or their position in the hand.

- So all that’s left is to choose the kicker, which can be any one of the remaining 48 cards.

So when we ignore order, there are \[ 13 \cdot 48 = 624 \] ways to get a four-of-a-kind. The probability is therefore \[ \frac{13 \times 48}{\binom{52}{5}} = \frac{624}{2,598,960} \approx .00024, \] which matches the answer from before. Notice how much simpler \(13 \cdot 48\) is, compared with the mental gymnastics needed to account for the order.

Essential Practice

- Prove the identity (3.2) by expanding the combinations using (3.1) and simplifying.

- Prove the identity \[ \binom{m}{k} = \binom{m}{m-k} \] in two ways: using a “story proof” (as in Example 3.1) and using algebra.

- Calculate \(\binom{m}{1}\). Why does this answer make sense?

- In Lesson 1, you calculated the probability of a “flush of hearts” in poker by counting the possible hands. There, you took order into account. Repeat the calculation by counting the possible hands where order does not matter.

- How many different 8-letter “words” can be formed by rearranging the letters in LALALAAA? (Hint: Model this situation using \(n=3\) draws from the box \(\fbox{\(\fbox{1}\ \fbox{2}\ \ldots\ \fbox{8}\)}\). The tickets that you draw correspond to the positions of the three Ls. So, for example, drawing \(\fbox{3}, \fbox{1}, \fbox{5}\) corresponds to the word LALALAAA. You still need to figure out whether the draws should be made with replacement and whether you should count different orderings of the same 3 tickets.)

- You toss a coin 60 times. Each toss results in two equally likely outcomes, heads or tails. What is the probability that you get exactly 30 heads in the 60 tosses? (Hint: To count the number of ways of getting exactly 30 heads, you need to count the number of ways of arranging 30 H and 30 Ts. The general strategy from the previous question may be helpful here.)

Additional Practice

- Use a story proof to show that \[ x(x-1) \binom{n}{x} = n (n-1) \binom{n-2}{x-2}. \] (Hint: Consider selecting a committee with a chair and a vice-chair.)