36 Central Limit Theorem

$$

$$

In Chapter 33, we saw that the exact distribution of the sample mean \(\bar X_n\) of i.i.d. exponential random variables is difficult to derive using convolutions. Unfortunately, moment generating functions are not much help either (Example 34.8). However, we can still derive accurate approximations to the distribution of \(\bar X_n\) when \(n\) is large.

In this chapter, we apply the theory from Chapter 35 to derive the asymptotic distribution of the sum and mean of i.i.d. random variables. Before we dive into the theory, we first illustrate the result using simulations.

In both examples above, we saw that distribution approached a normal distribution as \(n\to\infty\). This is no accident: the mean or the sum of i.i.d. random variables with (essentially) any distribution will be asymptotically normal! This result, which explains the ubiquity of the normal distribution in nature, is known as the Central Limit Theorem.

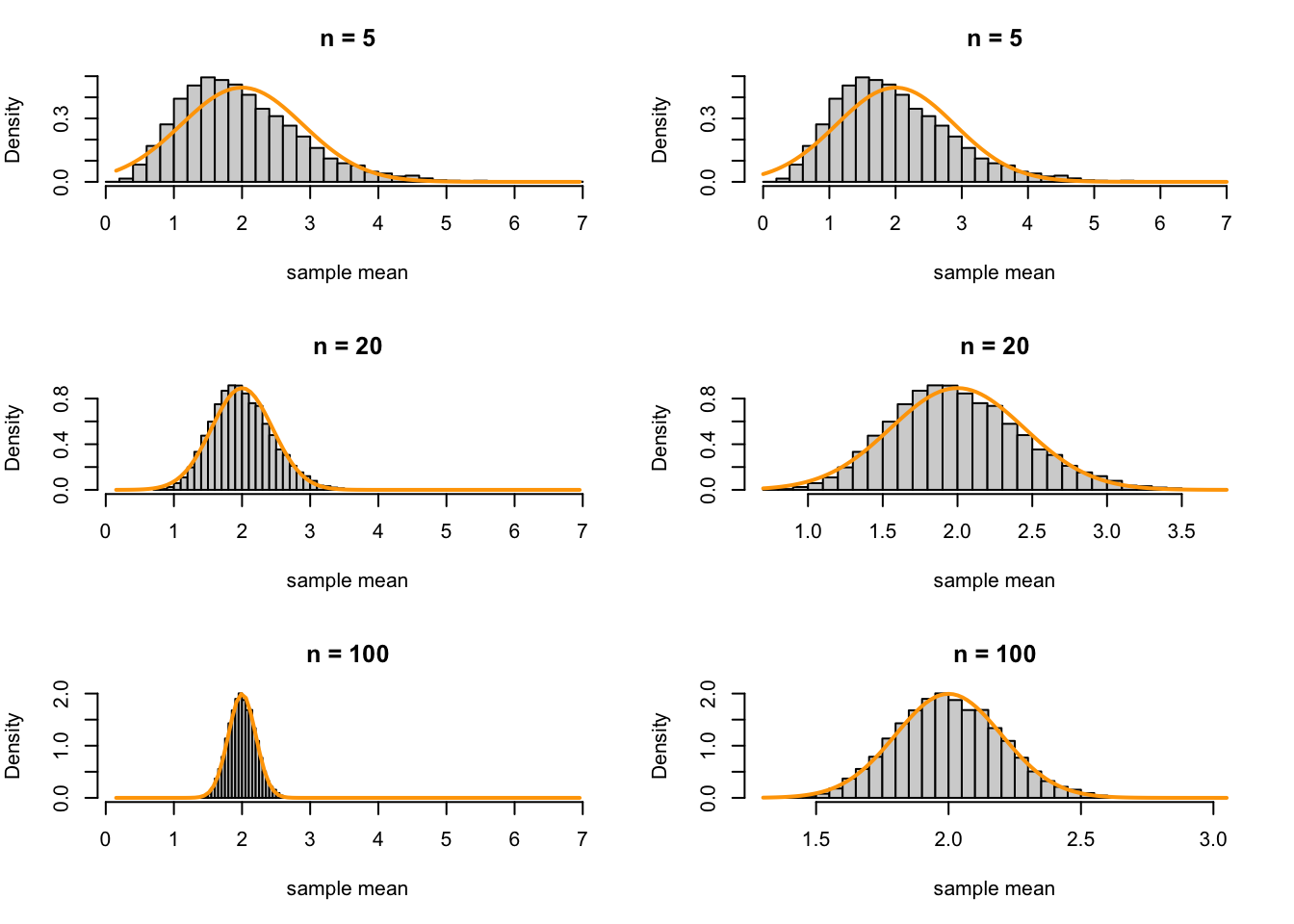

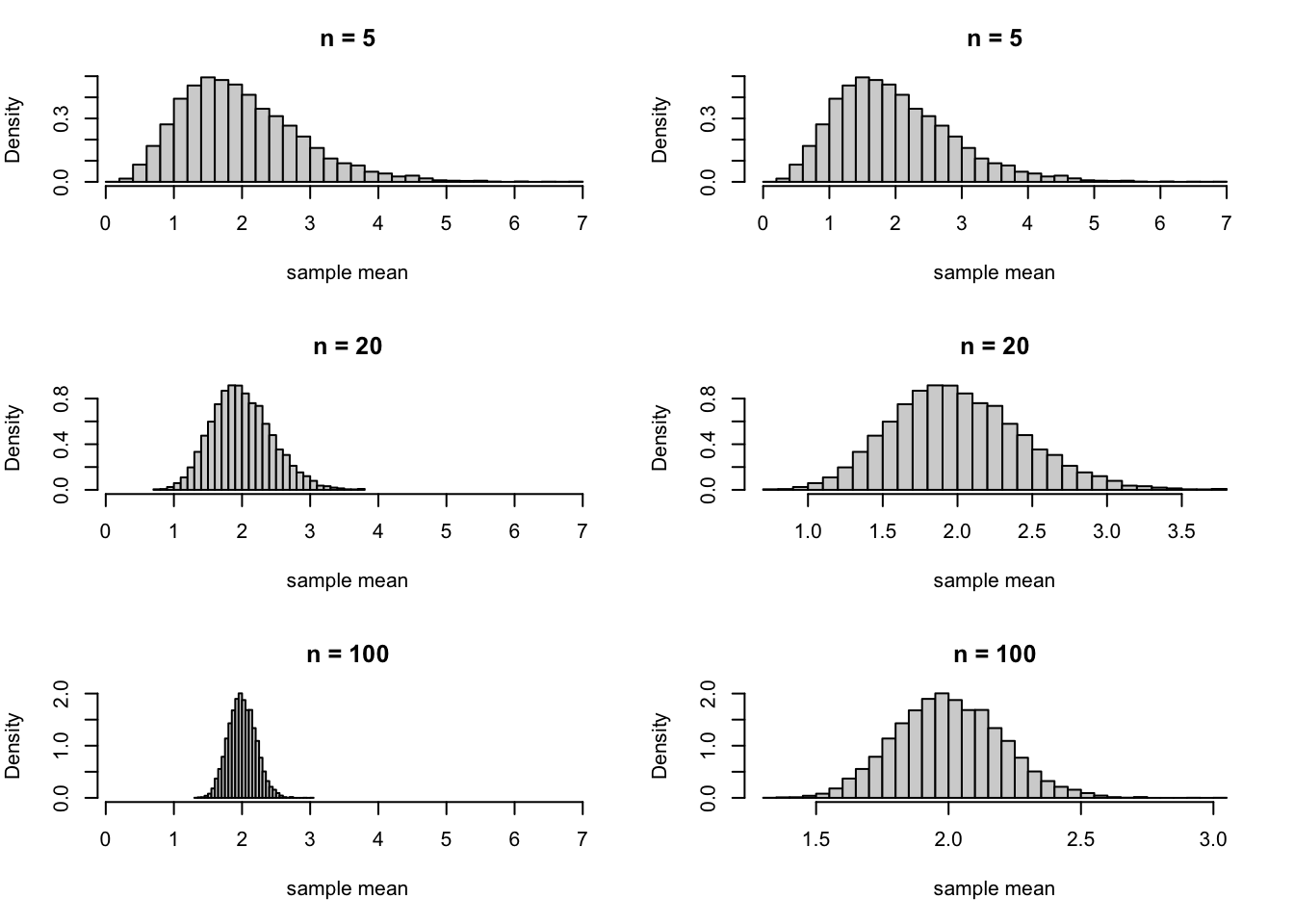

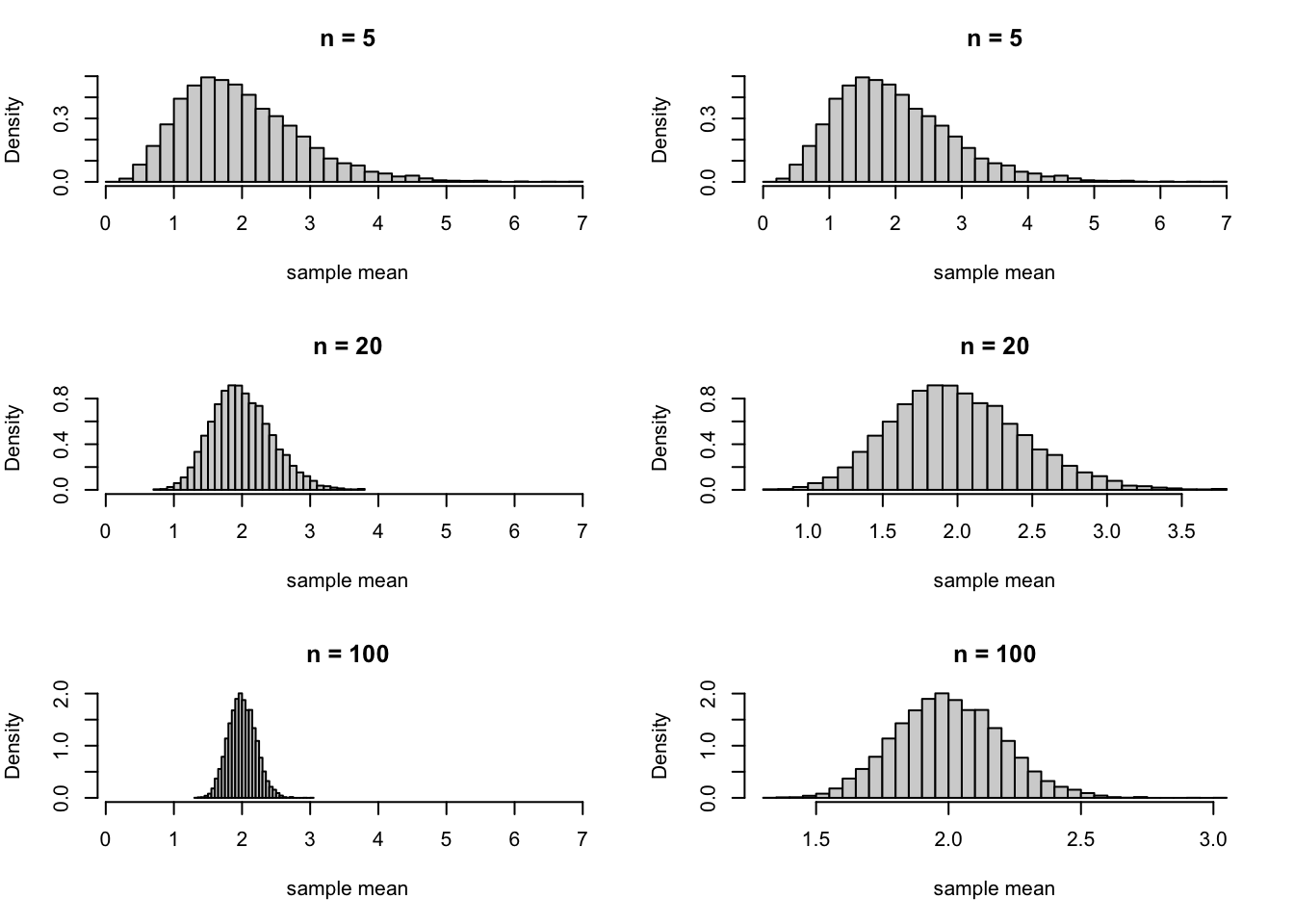

To make the statement precise, we revisit the case where \(X_1, X_2, \dots\) are i.i.d. \(\textrm{Poisson}(\mu=1)\) random variables. We know that \(\bar X_n\) converges in distribution to \(\mu\). This is represented by the left column of Figure 36.1. As \(n\to\infty\), the distribution collapses to a point mass at \(\mu = 1\).

However, if we zoom in at just the right rate, we can see that the distribution of \(\bar X_n\) around the mean \(\mu = 2\) is approximately normal. This is represented by the right column of Figure 36.1. To make this precise, we will consider the limiting distribution of \[ Y_n \overset{\text{def}}{=}\sqrt{n} (\bar X_n - \mu). \tag{36.1}\]

We know that \(\bar X_n - \mu \stackrel{d}{\to} 0\), but if we zoom in at a rate of \(\sqrt{n}\), then the resulting distribution will be nondegenerate. To see why \(\sqrt{n}\) is the right rate, consider the variance: \[ \text{Var}\!\left[ Y_n \right] = \text{Var}\!\left[ \sqrt{n} (\bar X_n - \mu) \right] = n \text{Var}\!\left[ \bar X_n \right] = n \cdot \frac{\sigma^2}{n} = \sigma^2, \] where \(\sigma^2 \overset{\text{def}}{=}\text{Var}\!\left[ X_1 \right]\). In other words, \(\sqrt{n}\) is exactly the right rate to ensure that the variance neither diverges to \(\infty\), nor collapses to \(0\).

Notice that Equation 36.1 can also be written in terms of the sum: \[ Y_n = \frac{1}{\sqrt{n}} \sum_{i=1}^n (X_i - \mu). \tag{36.2}\]

It turns out that this form of \(Y_n\) is more convenient for proving the Central Limit Theorem, but this expression is identical to Equation 36.1.

36.1 Statement and Proof

To find the limiting distribution of \(Y_n\), we will use MGFs and Theorem 35.3.

The Central Limit Theorem (or CLT, for short) is remarkable. In general, it requires no assumptions about the distribution of \(X_1\), other than that it has finite mean and variance. Although we assumed that \(X_1, X_2, \dots\) are i.i.d., there are other versions of the Central Limit Theorem that allow the random variables to be dependent (but not too dependent) and to have different distributions (but not too different). Because the Central Limit Theorem holds under such general settings, it explains the ubiquity of the normal distribution in nature, a point illustrated by the following video.

36.2 Applications

The Central Limit Theorem (CLT) can be used to obtain approximate answers to a wide variety of problems. In fact, we have already encountered one example.

The practical consequence of the Central Limit Theorem is that the distribution of a sum or a mean of a large number \(n\) of i.i.d. random variables can be approximated by a normal distribution with the same mean and variance. That is,

\[ S_n \overset{\text{def}}{=}\sum_{i=1}^n X_i \stackrel{\cdot}{\sim} \text{Normal}(n\mu, n\sigma^2) \tag{36.3}\] \[ \bar{X}_n \overset{\text{def}}{=}\frac{1}{n} S_n \stackrel{\cdot}{\sim} \text{Normal}(\mu, \frac{\sigma^2}{n}), \tag{36.4}\]

where \(\mu \overset{\text{def}}{=}\text{E}\!\left[ X_1 \right]\) and \(\sigma^2 \overset{\text{def}}{=}\text{Var}\!\left[ X_1 \right]\) are the mean and variance of an individual random variable in the sum.

In the next example, we use the Central Limit Theorem to explain the phenomenon seen in Figure 36.1.

In the last example, we show that the CLT can be useful, even when dealing with a random variable that is neither a sum nor a mean.

Let’s simulate the distribution of \(S_n\) from Example 36.5, assuming that the initial price of the stock is \(s_0 = \$50\).

Notice that the distribution of \(S_n\) is not symmetric, as we would expect a normal distribution to be. What is its approximate distribution? If we solve for \(S_n\) in Equation 36.5, we find

\[ \begin{align} \frac{1}{\sqrt{n}} \Big(\log \frac{S_n}{s_0} - n\text{E}\!\left[ \log X_1 \right]\Big) &\stackrel{d}{\to} \text{Normal}(0, \text{Var}\!\left[ \log X_1 \right]) \\ \log \left(\frac{S_n}{b_n}\right)^{1/\sqrt{n}} &\stackrel{d}{\to} \text{Normal}(0, \text{Var}\!\left[ \log X_1 \right]) & b_n = s_0 e^{n \text{E}\!\left[ \log X_1 \right]} \\ \left(\frac{S_n}{b_n}\right)^{1/\sqrt{n}} &\stackrel{d}{\to} e^{Y}, \end{align} \] where \(Y \sim \text{Normal}(0, \text{Var}\!\left[ \log X_1 \right])\). The distribution of \(e^Y\) is known as a lognormal distribution because its log is a normal distribution.

36.3 Exercises

Exercise 36.1 (Sum of ten dice) Suppose ten fair dice are rolled. Let \(X\) be the sum of the ten dice rolls. The exact distribution of \(X\) is difficult to determine.

- Use simulation to approximate \(P(25 \leq X \leq 40)\).

- Use the Central Limit Theorem to approximate \(P(25 \leq X \leq 40)\). How does this compare with the simulation?

- When approximating a discrete distribution (like the distribution of \(X\)) by a continuous one (like the normal distribution), it is often helpful to use a continuity correction. This means that we actually calculate \[ P(24.5 < X < 40.5) \] when using the normal approximation. Does this improve the agreement with the simulation?

Exercise 36.2 (Asymptotic distribution of \(\hat p\).) Let \(X \sim \text{Binomial}(n, p)\). Let \(\hat p_n = X / n\) be the MLE. Use the Central Limit Theorem to argue that \[ \frac{\hat p_n - p}{\sqrt{\frac{p(1-p)}{n}}} \stackrel{d}{\to} \text{Normal}(0, 1). \tag{36.6}\]

Exercise 36.3 (Normal approximation to the Poisson via the Central Limit Theorem) In Exercise 35.8, you showed directly that the \(\textrm{Poisson}(\mu=n)\) distribution can be approximated by a normal distribution when \(n\) is large. Show that this result is a special case of the Central Limit Theorem.

Exercise 36.4 (Asymptotic distribution of the normal variance MLE when mean is known) Let \(X_1, \dots, X_n\) be i.i.d. \(\text{Normal}(\mu, \sigma^2)\), where \(\mu\) is known (but \(\sigma^2\) is not). In Exercise 31.5, you derived \(\widehat{\sigma^2}\), the MLE of \(\sigma^2\).

Find a sequence of constants \(\{ a_n \}\) such that \[ a_n (\widehat{\sigma^2} - \sigma^2) \stackrel{d}{\to} \text{Normal}(0, 1), \]

Use this to approximate the probability that \(\widehat{\sigma^2}\) is within 10% of the true value \(\sigma^2\) (as a function of \(n\)).

Exercise 36.5 (Size of particles) Suppose a particle is subject to repeated collisions. On each collision, some of the particle breaks off. Suppose that the proportion broken off during each collision \(i\) is a random variable \(X_i\), where \(X_1, X_2, \dots\) are i.i.d. \(\textrm{Uniform}(a= 0, b= 1)\). Let \(Y_n\) be the proportion of the original particle that remains after \(n\) collisions.

Find a sequence of constants \(\{ a_n \}\) and \(\{ b_n \}\) such that \[ \left( \frac{Y_n}{b_n} \right)^{a_n} \stackrel{d}{\to} e^Z, \] where \(Z \sim \text{Normal}(0, 1)\). This explains why size distributions of particles tend to be modeled by a lognormal distribution.

Exercise 36.6 (Draymond Green’s three-pointers) It is April 13, 2025; the Golden State Warriors play their last game of the season against the Los Angeles Clippers. With both teams out of the playoffs, the Warriors decide that Draymond will attempt a three pointer every possession. Suppose Draymond’s probability of making an uncontest three pointer is \(0.2\) (for reference, Grayson Allen’s three pointer percentage was \(46.1\%\) in the 2023-24 season.)

Assuming Draymond attempts \(103\) three pointers (the average pace in the 2023-24 season for the Warriors) that are uncontested (since Clippers are very unmotivated defensively), use the Central Limit Theorem to estimate the probability the Warriors will score more than 60 points.

Remark. We may assume there are no free throws since there is no reason to foul Draymond.