47 Confidence Intervals

$$

$$

So far, we have focused mostly on point estimation, where the goal is to produce a single estimate of a parameter of interest. The problem with point estimation is that it ignores the uncertainty in this estimate. In this chapter, we will discuss how to report a range of plausible values of a parameter, representing the uncertainty in our estimate. This range of values is called a confidence interval and has a fundamental connection with the hypothesis tests from Chapter 46.

47.1 The \(z\)-interval

Recall Example 46.1, where the quality engineers take daily samples of \(n=5\) ball bearings from a production line. One day, the diameters of the ball bearings (in mm) are measured to be \[ X_1 = 10.06, X_2 = 10.07, X_3 = 9.98, X_4 = 10.02, X_5 = 10.09. \] It is assumed that \(X_1, \dots, X_5\) are i.i.d. \(\text{Normal}(\mu, \sigma^2 = 0.03^2)\).

In Example 46.1, we tested whether the production line was producing ball bearings that met the specification of \(\mu = 10\) mm. Alternatively, we can estimate \(\mu\), the mean diameter of ball bearings currently being produced by the line.

We know from Example 30.3 that the maximum likelihood estimate of \(\mu\) is \[ \bar X = 10.044. \]

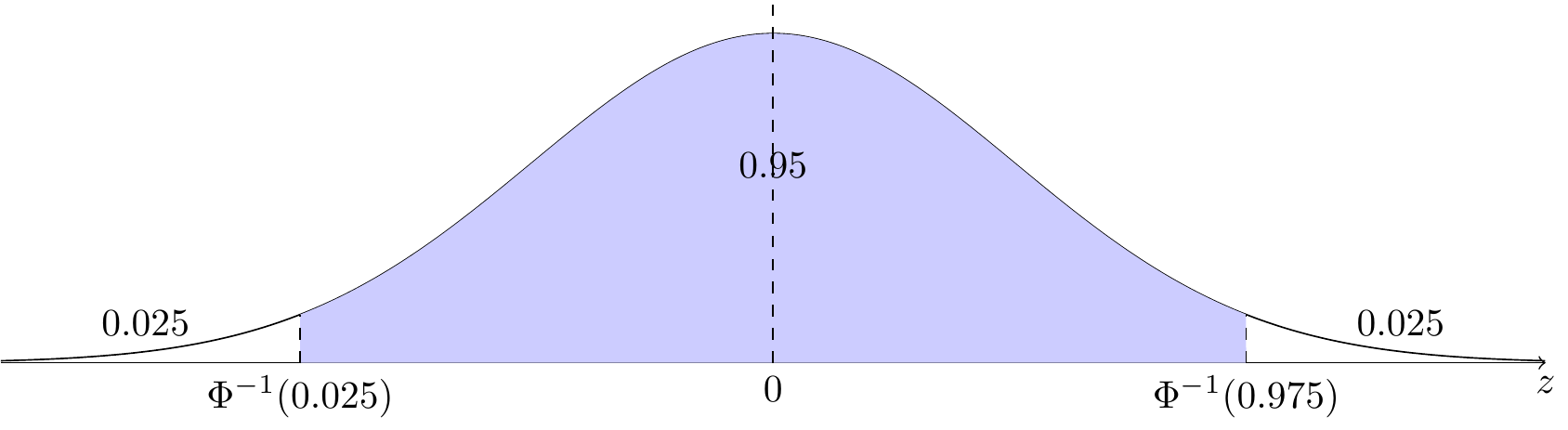

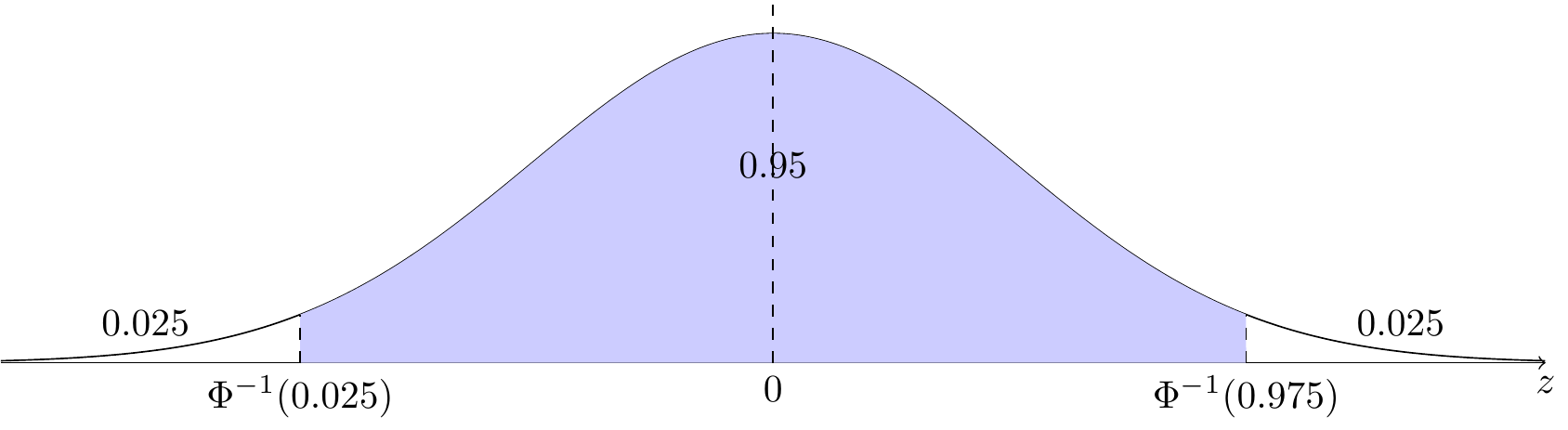

This is a point estimate of \(\mu\). We can quantify the uncertainty by reporting a 95% confidence interval. To do so, first observe that \[ Z = \frac{\bar X - \mu}{\sqrt{\sigma^2 / n}} \tag{47.1}\] is standard normal, so by definition, \[ P(\Phi^{-1}(0.025) < Z < \Phi^{-1}(0.975)) = 0.95. \] This is illustrated in Figure 47.1. (Note that \(\Phi^{-1}(0.975) = -\Phi^{-1}(0.025) \approx 1.96 \approx 2\).)

Substituting Equation 47.1 for \(Z\), we can rearrange the inequalities so that \(\mu\) is in the middle: \[ \begin{align} 0.95 &= P\left(\Phi^{-1}(0.025) \leq \frac{\bar X - \mu}{\sqrt{\sigma^2 / n}} \leq \Phi^{-1}(0.975)\right) \\ &= P\left(\Phi^{-1}(0.025) \sqrt{\frac{\sigma^2}{n}} \leq \bar X - \mu \leq \Phi^{-1}(0.975)\sqrt{\frac{\sigma^2}{n}} \right) \\ &= P\left(\bar X - \Phi^{-1}(0.025)\sqrt{\frac{\sigma^2}{n}} \geq \mu \geq \bar X - \Phi^{-1}(0.975)\sqrt{\frac{\sigma^2}{n}}\right). \end{align} \]

This leads to the startling conclusion that the random interval \[ \left[\bar X - \Phi^{-1}(0.975) \sqrt{\frac{\sigma^2}{n}}, \bar X - \Phi^{-1}(0.025) \sqrt{\frac{\sigma^2}{n}}\right] \] has a 95% probability of containing \(\mu\). This is called a 95% confidence interval for \(\mu\).

For the ball bearings data, a 95% confidence interval for \(\mu\) is \[ \left[10.044 - 1.96 \sqrt{\frac{0.03^2}{5}}, 10.044 + 1.96 \sqrt{\frac{0.03^2}{5}}\right] = [10.0177, 10.0703]. \tag{47.2}\] We say that we are 95% confident that \(\mu\) is between \(10.0177\) mm and \(10.0703\) mm.

We cannot say for certain whether \(\mu\) is between these two numbers or not, but we know that an interval constructed in this way will cover \(\mu\) 95% of the time. We can illustrate this via simulation. For the simulation, we have to assume a true value of \(\mu\).

About 95% of these intervals contain \(\mu = 10.02\) in this simulation. We say that this interval has 95% coverage. In practice, we only ever observe one of these intervals, and we have no way of knowing whether \(\mu\) is in that interval or not. However, we hope that our interval is one of 95% of intervals that do cover \(\mu\), as opposed to the 5% that do not.

The next proposition summarizes the results of this section, generalizing them to confidence levels other than 95%.

In the rest of this chapter, we will focus on the case where \(\alpha = 0.05\) (95% confidence intervals), although it is straightforward to generalize the results to other confidence levels.

47.2 Duality of Confidence Intervals and Hypothesis Tests

In general, a 95% confidence interval for a parameter \(\theta\) is a set \(C(\vec X)\), calculated from the data, which satisfies \[ P(\theta \in C(\vec X)) = 0.95. \tag{47.3}\] Note that the randomness is in the data \(\vec X\), not in the parameter \(\theta\).

How do we construct a confidence interval for a general parameter \(\theta\)? One way is to relate the problem to hypothesis testing. The 95% confidence interval that we constructed in Equation 47.2 did not cover \(\mu = 10.00\), which agrees with our decision in Example 46.1 to reject the null hypothesis that \(\mu = 10.00\). This is no coincidence. A 95% confidence interval will contain exactly those values of \(\mu\) that are not rejected by the corresponding hypothesis test.

Proposition 47.2 says that we can “invert” a hypothesis test to obtain a confidence interval and vice versa. If we invert the \(z\)-test from Section 46.1, then we obtain the \(z\)-interval above.

47.3 The \(t\)-interval

In the examples so far, we assumed the variance \(\sigma^2\) was known. What if it is not known?

In Section 46.2, we saw that for hypothesis testing, we can perform a \(t\)-test instead of a \(z\)-test. In the \(t\)-test, we replace \(\sigma^2\) by the sample variance \(S^2\). This introduces additional uncertainty, so instead of comparing to a standard normal distribution, we compare to a \(t\)-distribution.

We can use Proposition 47.2 to invert the \(t\)-test to obtain a confidence interval when \(\sigma^2\) is unknown. The result is called a \(t\)-interval.

Armed with the \(t\)-interval, we can calculate a 95% confidence interval for the average human body temperature.

In the examples that we have encountered so far, we started with a function of the data \(\vec X\) and the parameter \(\theta\), \[ g(\vec X; \theta), \tag{47.4}\] whose distribution is known and does not depend on \(\theta\). This is called a pivot (or pivotal quantity). In the examples above, the pivots were

- \(Z = \frac{\bar X - \mu}{\sqrt{\frac{\sigma^2}{n}}}\), which follows a standard normal distribution, and

- \(T = \frac{\bar X - \mu}{\sqrt{\frac{S^2}{n}}}\), which follows a \(t\)-distribution with \(n-1\) degrees of freedom.

Then, to obtain a confidence interval for \(\theta\), we used the quantiles of the pivot’s known distribution and rearranged the inequality so that the parameter \(\theta\) was in the middle.

47.4 Asymptotic Confidence Intervals

If \(X_1, \dots, X_n\) are not i.i.d. normal, then it is not easy to obtain a pivot. In these situations, there may not exist a confidence interval with exactly 95% probability of covering \(\mu\). However, it may still be possible to calculate an interval with approximately 95% coverage—at least when \(n\) is large, thanks to the Central Limit Theorem.

These asymptotic confidence intervals are known as Wald intervals. We can apply this to the skew die example (Example 29.4) from the very beginning of our foray into statistical inference!

The Wald interval is only guaranteed to have 95% coverage as \(n\to\infty\). How good is the interval for \(n=25\)? One way to answer this question is by simulation. To do this, we have to assume a particular value of \(p\) and generate many data sets of \(n=25\) observations.

Shockingly, a 95% Wald interval only covers \(p = 0.12\) about 81% of the time. Notice in particular that when \(\hat p = 0\), the Wald interval is \([0, 0]\), which is misleadingly precise. This example illustrates the dangers of relying on asymptotic results.

We can obtain an interval with better coverage by returning to first principles (Proposition 47.2). We start by deriving a test of \(H_0: p = p_0\). Then, we invert this test to obtain a confidence interval.

This is called the Wilson interval for the binomial proportion. (Wilson 1927) Comparing it with the Wald interval from Example 47.3, we see that:

- the Wilson interval is centered at \(\tilde p\) instead of \(\hat p\), and

- it uses a margin of error that differs by an offset of \(\frac{\Phi^{-1}(0.975)^2}{4n^2}\) and a factor of \(\left( \frac{n}{n + \Phi^{-1}(0.975)^2} \right)\).

These adjustments become negligible as \(n\to\infty\), which makes sense because the asymptotic coverage of the Wald interval is 95%. Nevertheless, these small adjustments improve the coverage dramatically for small values of \(n\), as the simulation below demonstrates.

Whereas the coverage of the Wald interval was 81%, the coverage of the Wilson interval is close to 95%! Furthermore, unlike the Wald interval, the Wilson interval gives a sensible answer when \(\hat p = 0\): \[ \left[0, \frac{\Phi^{-1}(0.975)^2}{n + \Phi^{-1}(0.975)^2}\right], \] which results in the interval \([0, 0.133]\) for the skew dice example.

The Wilson interval is still asymptotic; it relies on the Central Limit Theorem and is only guaranteed to have 95% coverage as \(n \to \infty\). However, because it was derived by inverting a hypothesis test that used the exact variance \(\sigma^2 = p_0 (1 - p_0)\) instead of an estimate, it tends to perform much better than the Wald interval for smaller values of \(n\).

47.5 Exercises

Exercise 47.1 (Agresti-Coull interval) In Example 47.4, we saw that the Wilson interval is centered around \(\tilde p\) instead of \(\hat p\). Agresti and Coull (1998) proposed a compromise between the simplicity of the Wald interval and the coverage of the Wilson interval. They proposed using the Wald interval with \(\tilde p\) instead of \(\hat p\) and \(\tilde n = n+\Phi^{-1}(0.975)^2\) instead of \(n\).

- Calculate the Agresti-Coull interval for the skew die example, and compare it to the Wald and Wilson intervals we calculated above.

- Write a simulation to evaluate the coverage of the Agresti-Coull interval. How does it compare with the Wald and Wilson intervals?

Exercise 47.2 (Confidence interval for an exponential mean) Let \(X_1, \dots, X_n\) be i.i.d. \(\text{Exponential}(\lambda)\). Consider forming a confidence interval for \(\mu \overset{\text{def}}{=}1/\lambda\).

- Form a 95% Wald interval for \(\mu\).

- Form a 95% confidence interval for \(\mu\) by deriving a test of \(H_0: \mu = \mu_0\) and inverting the test.

- Compare the coverage of the two intervals using simulation.